When the working class and peasantry took power in Russia in the October Revolution there were three main architectural tendencies which all competed with each other: realistic classicism, rationalism and constructivism. Later a fourth group so-called “proletarian architects”, organized itself into VOPRA (All-union Society of Proletarian Architects).

Classicism drew inspiration especially from ancient Greco-Roman models, the renaissance and Russian national architecture. Its leading names were Zholtovsky and Schuschev. This tendency will be discussed in a later episode. There was also a style of sorts in the late Russian empire known as “eclecticism”, a vulgarized type of architecture using pseudo-classical sources. Enemies of classicism often simply lumped them all into the “eclectic” category.

Constructivism was a tendency that arose mainly in the 1910s. It will also be discussed in more detail in the next episode. The main idea of constructivism is that form of the building emerges from its function, or represents its function. Constructivist buildings are often characterized by a highly geometric and industrial look, they are often designed to look like machines. Constructivism was often also called “utilitarianism” by its opponents, because constructivism tries to be oriented towards practice and at least theoretically puts the form of the building to a very subordinate position compared to its function, seemingly ignoring aesthetic qualities. The constructivists were mainly united in the “Organization of modern architects” (OSA).

The third tendency, rationalism, will be dealt with in this episode. The rationalists were a modernist tendency whose buildings are characterized by abstract geometric shapes. They were called “formalists” by their critics because they emphasized form and aesthetic quality more than functionality. Their view of aesthetic quality was not really based on beauty, but rather on “rationality”, hence the name “rationalism”. They considered that forms easy to perceive, or “requiring the least mental energy” were rational.

The rationalists were heavily inspired by the suprematism of Malevich and El Lissitzky, in fact El Lissitzky is often called a formalist/rationalist. They were also influenced by idealist gestalt psychology, empirio-criticism and the aesthetics of Kant. Rationalists were organized into ASNOVA* or Association of new architects. Later a split occurred where some of them constituted a new organization called ARU or association of architect urbanists.

*“The Association of New Architects (ASNOVA) was the first association of innovative architects. Nikolai Ladovsky, a VKhUTEMAS professor, was its theoretician and leader… The architects Vladimir Krinsky, Alexei Rukhlyadev, and Victor Balikhin were among ASNOVA’s founders. Lazar Lisitsky and Konstantin Melnikov stood close to the association.” (Andreĭ Vladimirovich Ikonnikov, Russian architecture of the Soviet period, p. 99)

Alongside the architectural debate between formalists, constructivists, classicist realists and the VOPRA, there was also a debate concerning city planning. Many architects, mainly constructivists but also some others, supported so-called “anti-urbanism” while many formalists supported urbanism. That debate will be discussed in a later episode.

The rationalists and constructivists were both very hostile to each other, however they had much in common and the buildings they designed look very similar, despite the different methods used. Eventually both of them were defeated by socialist realist architecture. In the course of several articles I will first provide a criticism of the erroneous anti-communist views of these tendencies, and then explain the marxist-leninist, socialist realist view of architecture.

The rationalists and constructivists are always portrayed very favorably by capitalist writers, who try to make them look good and use them to fight against socialist realism and marxism-leninism. Capitalist writers try to portray these modernist artists as superior artistically, and even more in accordance with marxism and the revolution. It is very characteristic that capitalist writers rarely focus on socialist realism, but the vast majority of literature on this topic focuses only on these modernist trends, such as rationalism and constructivism. But we must look at these trends critically in the light of facts.

According to marxist theory, the economy of a given society forms a base, on top of which arises an ideological superstructure. This ideological superstructure includes many forms of perceiving the world: philosophy, science, politics, religion as well as art. Art, according to marxism, is part of the superstructure, and is a specific form of social consciousness. Art is political and ideological. Even if the artist in question claims to not be involved in politics, he is still expressing some aspect of the ideological climate of the given society.

There is no “neutral art”, which is not ideological or political, and not expressing the interest of a given class. Art can be either more or less consciously political, or spontaneously political. Spontaneously political art is typically anti-communist, because in capitalist society the reactionary ideological hegemony of the decaying capitalist class prevails, and it continues to have a strong influence for a long time even after capitalism is toppled. Furthermore, the traditions of thousands of years of class struggle will continue to influence people for a long time.

Marxism denounces the capitalist theory of “art for art’s sake”, which states that art should not have any message or politics. Art for art’s sake is actually only a cover to hide the bourgeois nature of such supposedly neutral art. The rationalist/formalist organization ASNOVA actually claimed to support socialism, but they still described their formalist principles by the phrase “The measure of Architecture is Architecture.” (Anatole Kopp, Town and revolution; Soviet architecture and city planning, 1917-1935, p. 76) i.e. the equivalent of ‘art for art’s sake’ in architecture.

This was also pointed about a Soviet critic:

“The main slogan under the sign of which ASNOVA (created in 1923) came out was the slogan: “Measure architecture with architecture.” Comparing the speeches of formalists in other areas of art, we find an analogy to this slogan. “Literature for literature”, “art for art’s sake”, the thesis that art can be understood and explained only from its own foundations, the assertion of the complete autonomy of art from public life” (K. Mikhailov, “VOPRA—ASNOVA—SASS”, 1931)

ASNOVA also had many commonalities with the ultra-left theories of so-called Proletkult or “proletarian culture”. Proletkult was an organization and movement started by the revisionist Bogdanov, who’s theories Lenin had destroyed in his classic philosophical work Materialism and empirio-criticism. Bogdanov advocated the idealistic philosophy of empirio-criticism, which denied dialectical materialism and claimed that the objective world does not exist, or is not cognizable, so that all we can gain knowledge about are our own ideas and sensations. Bogdanov called this “proletarian philosophy”.

Bogdanov’s idea of “proletarian culture” or Proletkult, was that the workers must reject all traditions, that the proletariat must create an absolutely new culture with nothing in common with past history. This basically anarchistic idea is deeply anti-marxist. Marxism considers that the workers must absorb and master all past human culture, and critically evaluate it, taking its best elements and developing them further. The future culture can only be built on top of the past.

Socialism will be built by taking the industry and science developed in capitalism, and not by destroying industry and science. The erroneous aspects of past science and industry will be left behind, and the usable aspects will be critically re-worked and developed further. Lenin said:

“The task of Marxists… is to be able to master and refashion the achievements of these [bourgeois scientists]… and to be able to lop off their reactionary tendency, to pursue our own line and to combat the whole line of the forces and classes hostile to us.” (Lenin, Materialism and Empirio-Criticism)

“Only a precise knowledge and transformation of the culture created by the entire development of mankind will enable us to create a proletarian culture.” (Lenin, The Tasks of the Youth Leagues)

So-called “avant-garde” abstract art movements follow an anarchistic method. They think they can create something “entirely new”, totally rejecting everything from the past. In reality, such art movements have always merely copied reactionary imperialist fads and have never created anything original at all. The same goes for ASNOVA.

Marx himself considered ancient Greek art to still be “in certain respects regarded as a standard and unattainable ideal” for contemporary art (A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy).

ASNOVA followed Bogdanov’s idea that all past culture must be rejected, both good and bad:

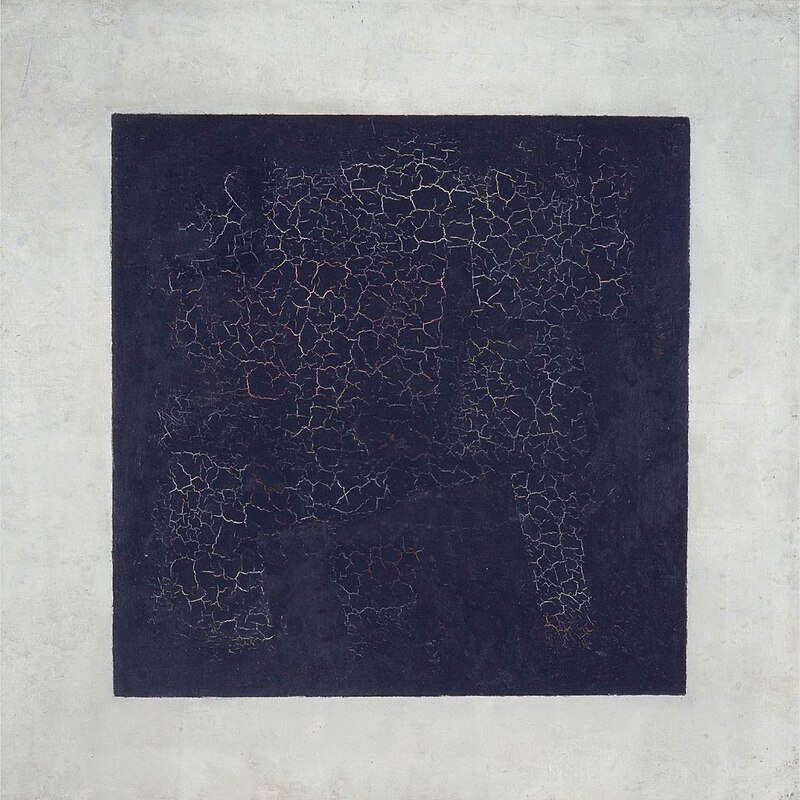

“ASNOVA’s concept of architecture remained deeply rooted in Kasimir Malevich’s Suprematism. This concept, in turn, was based on a rather vulgar interpretation of Marxism. According to the suprematists, each mode of production generated not only a ruling class but also an official artistic style supported by that dominant social class. Deviations from that official style were the products of subordinate classes. All art, prior to the rule of the proletariat, therefore, manifested the ideology of some class. But the revolution was to bring about the destruction not merely of the bourgeoisie, but of all classes as such. Consequently, the art of the proletarian revolution must be the expression not merely of another style but of absolute, eternal, “supreme” values”” (Hugh D. Hudson, Blueprints and blood: the Stalinization of Soviet architecture, 1917-1937, p. 24)

As Hudson says, ASNOVA relied on the idealist views of Malevich. Malevich believed that there are certain “absolute”, “eternal”, “supreme” values, which are class-neutral and ahistorical. In his paintings, in works such as Black square, Malevich tried to express these supreme ideas by maximum abstraction, with only two-dimensional geometric shapes with flat colors.

“The association members described themselves as rationalists, seeing the chief task in organizing and rationalizing the perception of architecture.” (Andreĭ Vladimirovich Ikonnikov, Russian architecture of the Soviet period, p. 99)

For them, this rationalizing meant something quite specific, which again was drawn from suprematism:

“ASNOVA was under an especially strong influence of Malevich’s Suprematism. His advocation of austerity as the measure of art’s value provided the basis for the principle of “psychological energy”, seen by Ladovsky as the chief criterion of form-shaping in architecture. He attempted to base ASNOVA’s rationalistic aesthetics on data of experimental psychology, or “psychotechnics”” (Ikonnikov, p. 99)

The leading figure of ASNOVA, Ladovsky wrote that: “Modern aesthetics, is about saving the psychophysical energy of man.” (“Izvestia ASNOVA”, 1926, Ladovsky, “The basis for constructing a theory of architecture.”)

As a marxist critic wrote:

“it is necessary to establish how they understand “rationality” itself. “Architectural rationality,” writes one of the leaders of formalism, N. Ladovsky, “is based on an economic principle in the same way as technical rationality.

The difference lies in the fact that technical rationality is the saving of labor and material when creating an expedient structure, and architectural rationality is the saving of mental energy when perceiving the spatial and functional properties of the structure. The synthesis of these two rationalities in one structure is rational architecture” (“Izvestia ASNOVA”, 1926 Ladovsky, The basis for constructing a theory of architecture.)

Already here the moments of an idealistic understanding of architecture are striking. Architecture is reduced to pure technology and pure form, and form is made dependent on perception, the basic thing that we consider to be decisive for architecture, its dependence on certain forms of social relations, on socio-economic conditions, is thrown out.” (A. I. Mikhailov, “Formalism in Soviet architecture”, 1932)

“We can find the development of these provisions in a number of formalists. Their philosophical essence goes back to the aesthetics and philosophy of Kant, who puts forward form as the basis of art and aesthetic judgment, excluding the latter from the socio-practical environment. However, they go back to Kant’s aesthetics for the most part not directly, but through the latest idealistic movements. The connection with modern idealist philosophy is easily revealed if we compare the main provisions of Machian philosophy with the provisions of the formalists. The principle of saving psychic energy corresponds to Mach’s principle of “least waste of effort”, reducing form to sensation – the primacy of sensation in Mach, etc.” (A. I. Mikhailov, “Formalism in Soviet architecture”, 1932)

The marxist critic correctly points out the idealist character of ASNOVA’s theories. They correctly point out that the suprematist principle of “economizing mental energy” is the same as that of the machists (i.e. empirio-critics).

He calls the aesthetic views of ASNOVA Kantian, because according to the classical idealist Kant, forms of consciousness and forms of perception are eternal, non-class and ahistorical. According to Kant’s idealist views, aesthetics are not determined by societal factors, but are eternal and are determined by the very structure of our consciousness – this is the exact view of the ASNOVA rationalists, in fact it is the core of their theory.

“formalists reduce architectural form to perception. For them, this architectural form exists only in perception and is subordinate to it. Again, there is no special need to prove that here the formalists are simply applying the old idealistic position that being, reality, is determined by consciousness.

The materialist will seek an explanation for the evolution of architecture in specific historical, social conditions, while the formalist will look for the eternal laws of perception, which in his opinion determine the change of architectural forms. The eternal laws of perception, rooted in the unchanging nature of man (“generally” devoid of any social connections), plus the artistic will of the architect, based on knowledge of these laws, are the “factors” that determine the work of the architect for the formalists…

How should “artistic will” be expressed and what is it based on? The “rationalists” readily answer this question.

“An architect-artist”, writes Dokuchaev, “in addition to knowledge of the construction and technical side of construction, must at the same time be an artist who has undergone a rational school of studying the needs of the human eye and who knows how to methodically satisfy these needs. The foundations of our perception rest on laws and principles that are deeply objective in nature. The psychophysiological foundations of our perception do not change so quickly and do not depend on fashion. Therefore, the architect-artist must raise (and not follow fashion) the consumer to understand these objective laws of the art of architecture, which take into account our ability to perceive forms and space. The technique that architecture uses must itself be subordinate in its design to the principles of architecture)”. [Dokuchaev – “Modern Russian architecture and Western parallels”, “Modern Art”, 1927, No. 2.]

What do all these provisions essentially mean? Essentially, they set out a program of idealistic bourgeois aesthetics and try to impose it on the proletariat under the guise of the “eternal laws” of perception, and hence the “eternal” laws of harmony, rhythm, etc.

The anti-Marxist, anti-proletarian character of such a program is completely obvious.” (K. Mikhailov, “VOPRA—ASNOVA—SASS”, 1931)

“The entire history of idealism in art was full of endless tricks to create some “eternal” laws of art that ignored its social conditioning.

For example, one of the founders of psychological aesthetics, Fechner in the second half of the twentieth century wrote about the six main laws of perception of peace and beauty (according to Fechner, these laws are as follows: intensity of aesthetic threshold, intensification of impressions, unity, lack of contradictions, clarity and associations). Close to them are… the “five pairs of concepts” by Wölfflin – one of founders of modern formalist art criticism (linear flatness – picturesqueness, flatness – depth, closedness – openness This form, plurality – unity, absolute and relative clarity). Theorists from ASNOVA found themselves captive of these anti-scientific, metaphysical ideas about art.” (Mikhail Tsapenko, On the realistic foundations of Soviet architecture, pp. 127-128)

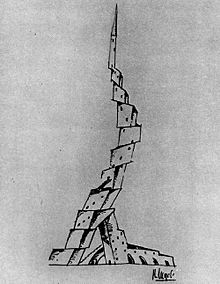

“Extreme formalists from ASNOVA placed special emphasis on geometric expressiveness of form, as a manifestation of absolute static and dynamic properties. As we have already seen, in a number of cases geometrical properties were given a naive-symbolic social interpretation (like the spiral expresses the “idea of revolution,” etc.). But soon even such a primitive public understanding of architecture seemed to formalists as something too “social”. Their further experiments in the field areas of psychological perception of architecture come down to the fact that architecture must express abstract ideas from the world of physics and geometry: ideas of gravity, elasticity, rhythm, repetition, etc.” (Tsapenko, pp. 128-129)

Tsapenko points out that ASNOVA rationalists originally gave crude symbolistic meanings to various geometric shapes. Such as, a spiral means revolution, or like in El Lissitzky’s poster Beat the whites with the red wedge, the capitalist whites are represented by stationary spheres and squares, while the communist reds are represented by dynamic and moving triangles. But later even this crude social symbolism became too concrete for the rationalists, and they retreated even further away from real life, even further into abstraction, trying to express in their works only such “eternal”, “supreme” values as ‘gravity’, ‘movement’, ‘contrast’ etc.

Marxist critics pointed out how utterly ASNOVA was detached from the reality of socialist construction, and how they worshiped abstract form isolated from social content:

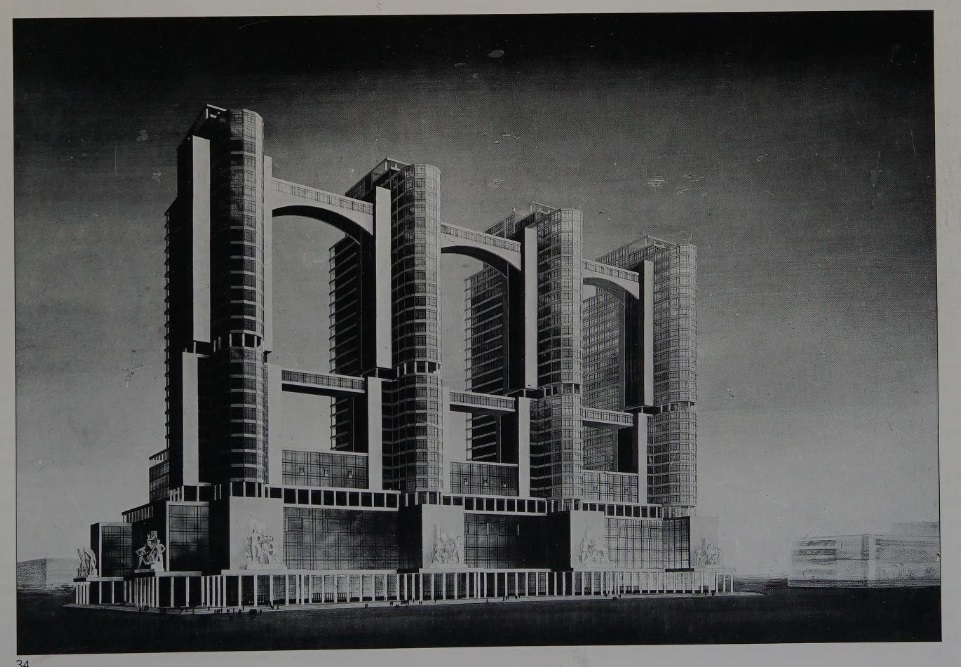

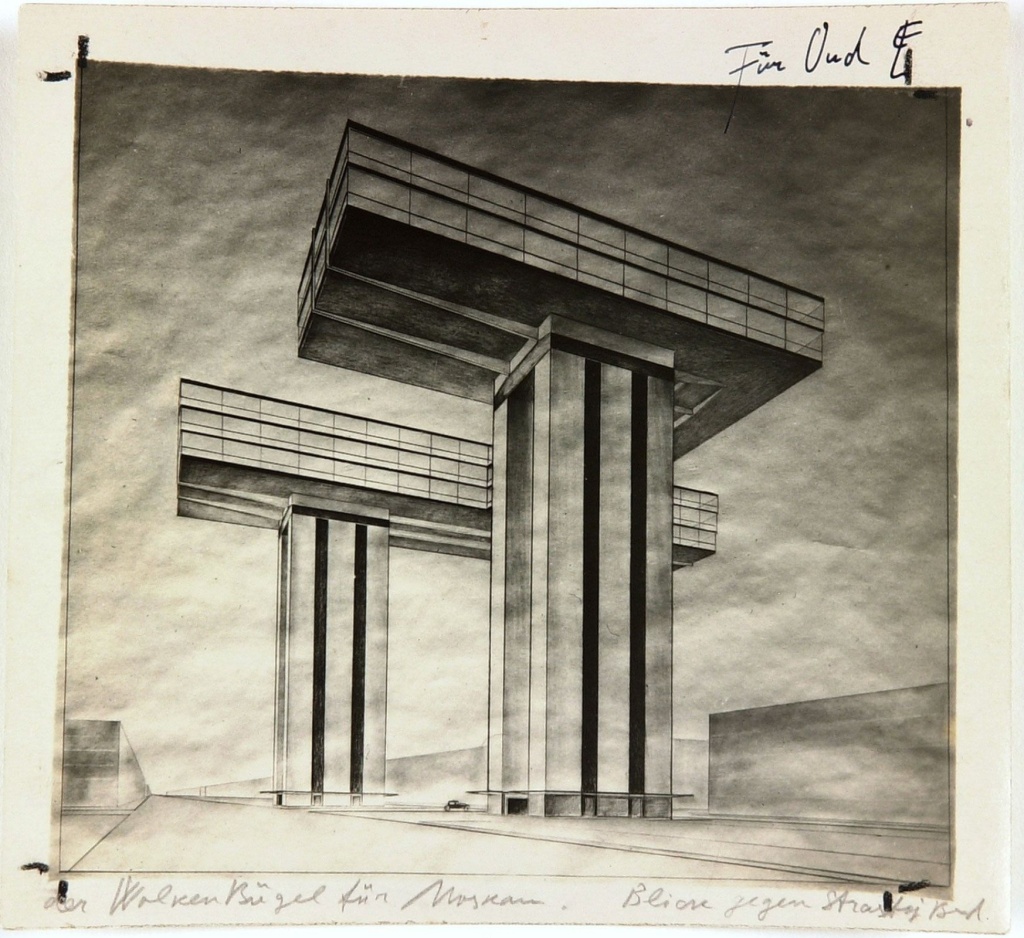

“At one time, Izvestia ASNOVA published a very interesting project by El Lissitzky in this regard: a series of skyscrapers for Moscow.

The skyscraper, in the shape of the letter H, is given in this project horizontally raised above the ground on stilts. How does the author explain this unusual form of residential structure? “Until the possibilities of completely free soaring have been invented,” he writes in his explanation, “we tend to move horizontally, not vertically. Therefore, if there is no space on the ground for horizontal planning in a given area, we raise the required usable area onto stilts.”

“I proceeded from the balance of two contrasts:

a) the city consists of atrophying old parts and growing living, new ones; We wanted to deepen this contrast;

b) give the structure itself spatial balance as a result of contrasting vertical and horizontal stresses” [See “Izvestia ASNOVA”, 1926, “Series of skyscrapers for Moscow” by El Lissitzky.]

Thus, the task was based on two points:

a) this form of technology for orientation, human movement in space, which fully corresponds to the above-cited position of the formalists that architecture serves “the highest technical need of man – to navigate in space”;

b) the formal-aesthetic task of achieving a contrast of horizontal and vertical tensions, which corresponds to the fetishism of abstract form.

But the result was a structure that stands in stark contrast to the possibilities for urban reconstruction that exist in the USSR, a refusal to develop new types of housing that correspond to new social relations.

El Lissitzky did not try to pose all these questions. All this turned out to be unimportant for him. At the same time, masked by the abstractions of “orientation in space” and the search for abstract formal relations, El Lissitzky gave a solution, the class content and direction of which are beyond doubt.” (A. I. Mikhailov, “Formalism in Soviet architecture”, 1932)

Such views of ASNOVA became increasingly more of a problem as socialist construction advanced, because they fell behind from current architectural tasks, and the importance of practical tasks was emphasized more and more, especially after the criticism of the Deborin school in philosophy (see my article on the Deborinists).

Marxism also rejects formalism, the worship of form without content, because it is tied to the theory of “art for art’s sake” and is anti-realistic. Practically all abstract art is formalistic. Instead of formalism, marxism advocates socialist realism, which portrays reality in a truthful way, elevates people’s class consciousness and gives them a way forward.

A writer from VOPRA wrote:

“We especially emphasize the groundless fantasy and utopianism of formalist architects in the field of solving social and everyday problems of today and the idealistic nature of their theories and methods of work.” (K. Mikhailov, “VOPRA—ASNOVA—SASS”, 1931)

At the first congress of Soviet architect K. S. Alabian criticized “the early years of Soviet architecture, years of “paper architecture” divorced from the demands of the people and cut off from real construction. The ultimate product of these years was merely “formalistic sleight of hand.” … Alabian turned to ASNOVA, “which flowed from the aforementioned cult of abstract form.””(Hudson, p. 191)

Certainly El Lissitzky’s “horizontal skyscraper” is a perfect example of such purely “paper architecture”. It should also be noted that such paper architecture did not arise by chance, but due to a combination of factors:

1) a result of the influence of western bourgeois art,

2) a result of idealist petit-bourgeois views, detached from reality,

and to a significant degree,

3) the result of the economic situation of the country at the time. During the civil war and early NEP years only very little actual construction took place because of the country’s poverty. Architects from a bourgeois background and with bourgeois ideas had time to create utopian designs on paper, but no resources to actually build.

Of course even during this period, many reasonable designs were also created, and some were later utilized. Certainly the economic situation which prevented real construction caused the modernist architects to become more and more “experimental” and detached from reality in their designs, because they didn’t have to worry about actually trying to make their designs a reality. When socialist construction was put on the order of the day, and even when economic reconstruction was demanded, that kind of architectural ideas were hopelessly inadequate.

The ASNOVA notion that architecture doesn’t deal with specific social goals, with materials etc. but with abstract “space” and that “man’s highest need is navigation through space” also came under attack by marxists. It was revealed to be completely idealist and out of touch with reality:

“VOPRA believes that architecture should meet specific social needs and express specific content; ASNOVA leaders state that architecture should “serve the highest technical need of man – to navigate in space .”

VOPRA comes from the demands of the proletariat as a class subject of proletarian architecture, ASVOVA – from the “objective” laws of vision, from “spatial logic”, “economy of mental energy”.

VOPRA – for conveying through architecture the deepest intentions, aspirations and ideas of the working class.

ASNOVA – for the “eternal”, objective beauty of forms that speak of “power and weakness, greatness and baseness, finitude and infinity” (typical fetishes of preaching idealistic aesthetics)… In fact, they preach and adapt idealistic-bourgeois theories…

Kant’s doctrine… that aesthetic pleasure does not stand in connection with practice, disinterestedly, etc., Wölfflin’s “categories of vision”, the reduction of the evolution of art to the “objective” laws of this vision ( eyes), Fiedler’s autonomy of art, Hildebrand’s provisions on the certainty of our relationship to the outside world by the knowledge and representation of space and form, and the understanding of art as a pure visual form – all this found its place in the theory and method of the “rationalists”.” (K. Mikhailov, “VOPRA—ASNOVA—SASS”, 1931)

During the Debate between the dialectician school of Deborin and the mechanists, ASNOVA allied itself with the Deborinists and attacked its rivals, the constructivists, as mechanists. While it was not incorrect to accuse the constructivists of mechanism, the formalists themselves were not by any means free from serious mistakes. (Hudson, p. 80)

ASNOVA waged an ultra-leftist campaign against their constructivist rivals, interpreting Deborin’s dialectics in a voluntarist way, claiming that all tradition must be destroyed and using class-conflict terminology, while the constructivists utilized Bukharin’s theories of equilibrium and class-harmony.

“Rejecting OSA’s stress on interclass cooperation in solving concrete problems of building a socialist environment, ASNOVA parroted the Stalinist cliches regarding the class-ideological functions of architecture and the need for architecture to symbolize an idea.” (Hudson, p. 82)

It is completely dishonest for Hudson to call ASNOVA’s views “stalinist cliches” on class-ideological functions of architecture, because ASNOVA advocated theories of non-class – i.e. bourgeois – aesthetics, and because the only sense in which ASNOVA understood class conflict, was metaphysical and Bogdanovist. They believed that class-conflict means the destroying of all tradition. They considered that each new ruling class simply destroys the past, instead of critically assimilating, re-working and developing it.

That is not to say that there was nothing positive to the rationalists. As stated by a marxist writer, Ladovsky split from ASNOVA and created a new organization, the ARU in 1928. The ARU attempted to be more praxis-oriented, though it ultimately failed in this regard:

“In 1928 Ladovsky and a few other members left ASNOVA which they considered too involved in abstract theory. They formed the Association of Urban Architects, ARU, in order to concentrate on planning methods essential to the reconstruction of the state and particularly the development of nationalized land. They considered architecture as a socialist and psychological means of educating the masses. They advocated courses in urbanism and the popularization of their aims. Projects were carried out by Ladovsky and students of VKHUTEMAS (a theatre in Sverdlovsk, a housing estate for the Telbesk factory, Trubnoy Square in Moscow and plans for the development of middle Asia).” (V. Khazanova, “Soviet Architectural Associations 1917-1932” in Building in the USSR, 1917-1932, ed. O. A. Shvidkovsky, p. 22)

“By the beginning of the reconstruction period, the formalists began to come closer to practice, and the association of urban architects [ARU] separated from them (1928)…

Positive changes were manifested in the fact that the formalists who joined the ARU set themselves specific tasks of participating in the planning and redevelopment of cities. They tried to set these tasks in accordance with the requirements of socialist construction. Listing the main features of a city in a socialist system, in contrast to the West, they point to a number of socio-economic and political aspects that must be taken into account as the basis for planning work… despite individual shifts, the formalists, renaming themselves “urban architects,” remained in their old position on the main, decisive issues.” (A. I. Mikhailov, “Formalism in Soviet architecture”, 1932)

Also, rationalism, while upholding a rather warped view of aesthetics, still did not deny aesthetics to the same degree as constructivism:

“Rationalism lead by N. A. Ladovsky… while sharing many of the constructivist principles, was more favourable to classical heritage and allowed for some decorativity.” (A. Bazdyrev, “History of Soviet Architecture: From Palaces to Boxes)

Though ASNOVA’s views were completely confused, some of their ideas were not wrong. Their ideas such as unity of buildings and their environment, the unity of ensembles instead of individual buildings etc., were correct and had dialectical features. Their rivals, the constructivists, believed that the function of the building ought to completely determine its form, and design should be done from “inside out”, one building at a time, disregarding whether the building fits its environment.

Still, ASNOVA’s views were idealist and anti-marxist to the core and ought to be rejected. While sharing many things with constructivism, rationalism had even less positive qualities.

IN SUMMARY

ASNOVA’s views were eventually rejected by marxists and the architectural community both for theoretical and practical problems.

-ASNOVA tried to develop a “rational” aesthetics, which reduced aesthetic value to the crude idea that a building which requires the least mental energy to perceive, is rational. This was based on idealist theories derived from suprematism and reactionary philosophy. It was analogous to empiriocriticist views. ASNOVA spent a lot of effort studying perception through laboratory methods, but aesthetic beauty cannot be measured like that.

-ASNOVA’s view of aesthetics was incredibly flawed because it believed that since aesthetics was purely rooted in laws of perception, it should therefore remain the same for all classes and all times. It was thus a normative type of aesthetics, but like so often happens, it didn’t correspond to reality at all. No society has ever followed the guidelines of ASNOVA. This theory is anti-marxist since it is “class-neutral” and ahistorical. A materialist understanding must recognize that aesthetics develops historically based on material causes and reflects class interests, though it shouldn’t be understood simplistically.

-ASNOVA actually held the suprematist view that each class has its own style of art, which is an oversimplification. But ASNOVA considered this irrational and focused on creating the art of the classless society. This further put them out of touch with reality because classes still existed. This is derived from the suprematist notion that art must not reflect material reality, but “supreme values” beyond the material world, or outside the material world. Marxists could not accept such idealism.

-These ideas eventually become reduced to crude symbolism where abstract shapes are given some ideological meaning. ASNOVA was correct to consider that buildings have an ideological effect on the viewer, but they understood this in such a crude form it became useless. Nobody is going to see a triangular building and be convinced that communism is correct. Its not so simple. This topic will be discussed further in a later episode. Furthermore, ASNOVA even retreated from this to expressing even more abstract “supreme values” such as abstract gravitation, motion, contradiction, etc. which is truly just “formalism”, i.e. the worship and fetishization of experiments with forms for their own sake.

-All these criticisms showed that rationalism was totally unacceptable and unworkable, despite their attempts to justify it by appealing to marxism, and I have not even contrasted ASNOVA to socialist realism yet. When I start to discuss socialist realism, it will become even more apparent how ASNOVA meets none of the criteria that was required. However, the failure of ASNOVA is blatant even without discussing realism at all.

-Despite all these philosophical and theoretical criticisms, the most important flaw with rationalism was that it was simply not feasible or practical. Practice was always the most important criteria for the Soviet Union. Constructivism was criticized theoretically, but always received some praise for its practical achievements. ASNOVA had much fewer such achievements. Their ideas were often impossible to implement and were a hindrance. As such they had absolutely zero chance of winning the architectural debate.

ASNOVA “remained, until its demise, a relatively small grouping based mainly in Moscow.” (Ikonnikov, p. 99) and its leading architects eventually adopted more workable ideas. Ladovsky and El Lissitzky both adopted socialist realism and contributed to socialist construction.

SOURCES:

Andreĭ Vladimirovich Ikonnikov, Russian architecture of the Soviet period

K. Mikhailov, “VOPRA—ASNOVA—SASS”, 1931

Lenin, Materialism and Empirio-Criticism

Lenin, The Tasks of the Youth Leagues

Marx, A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy

Hugh D. Hudson, Blueprints and blood: the Stalinization of Soviet architecture, 1917-1937

Ladovsky, “The basis for constructing a theory of architecture”, Izvestia ASNOVA, 1926.

A. I. Mikhailov, “Formalism in Soviet architecture”, 1932

Mikhail Tsapenko, On the realistic foundations of Soviet architecture

“Series of skyscrapers for Moscow” by El Lissitzky, “Izvestia ASNOVA”, 1926.

V. Khazanova, “Soviet Architectural Associations 1917-1932” in Building in the USSR, 1917-1932, ed. O. A. Shvidkovsky

A. Bazdyrev, “History of Soviet Architecture: From Palaces to Boxes

Hudson and Khazanova are anti-communist bourgeois writers, Ikonnikov is a Soviet revisionist writer. All the other sources are recommended reading, though the VOPRA position is also not entirely correct and will be explained in a later episode. Tsapenko and Bazdyrev are particularly good sources.